Intro

Once upon a time I decided to read and summarize whatever the generally assumed foundational papers of UX are. In my head it looked like this beautiful, quickly paced blog series where I read a ton of literature and become really acquainted with what all the big names of 1980’s usability research were saying back then.

Well, should have expected that foundational papers tend do be quite comprehensive and packed. Point being: This is part 2 of the show (part 1 here), and we are still at our first paper, Designing for Usability: Key Principles and What Designers Think. We are not finishing it today, either.

Gould and Lewis development model

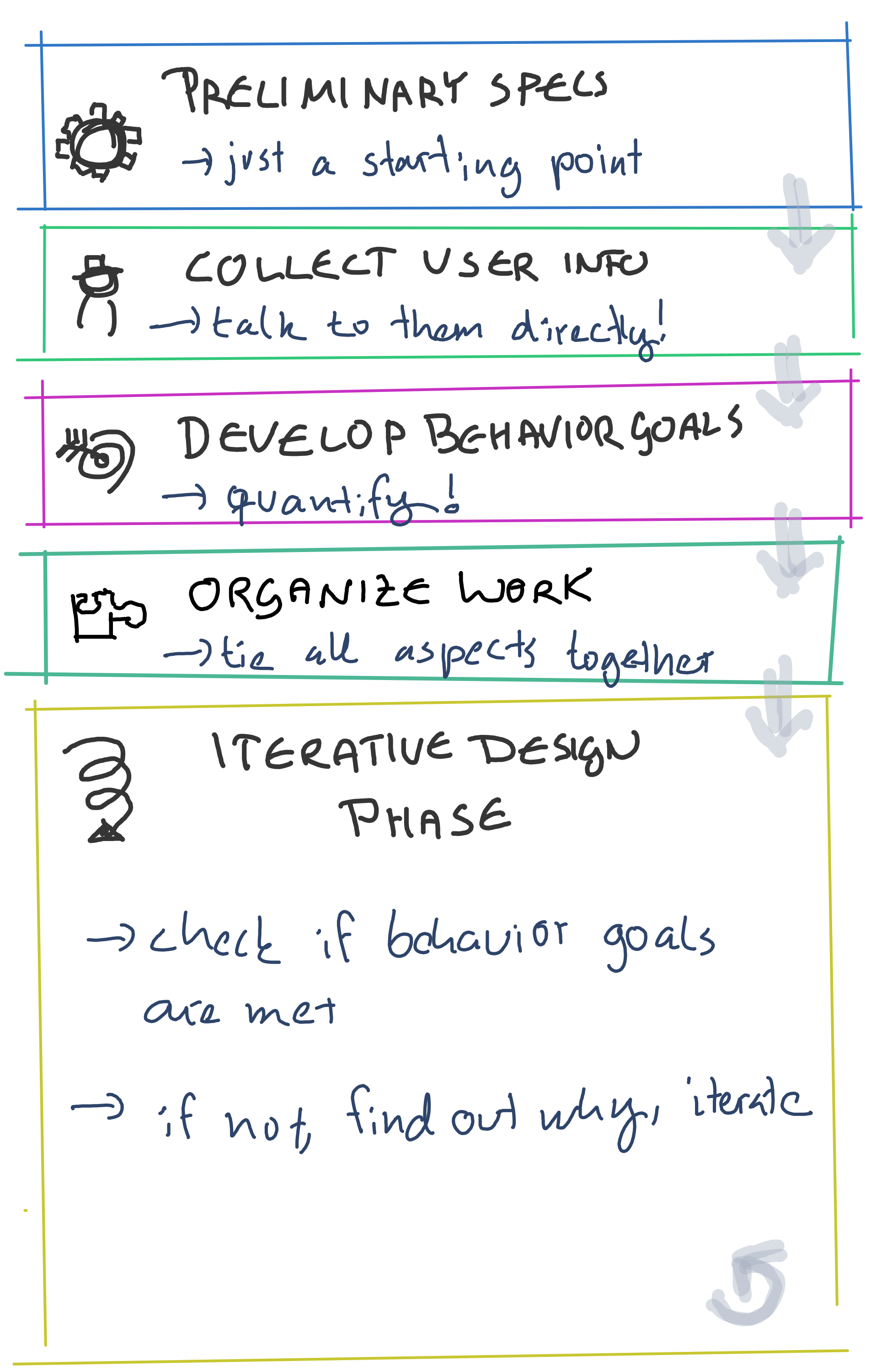

So after quite cheekily proving the dire need for their research, Gould and Lewis basically go more in-depth with their model. Although they humbly call this section “An Elaboration Of The Principles”, I think it is basically an overview of their unique approach and probably deserves more than this shitty sketch:

My understanding how Gould & Lewis do stuff

The base structure of the model is straight-forward: It is basically five steps, with the last one actually looping.

I am not an expert in project management theory, so I won’t be so presumptuous as to offer grand commentary here, but I do urge you to compare this to Agile or Waterfall models you worked with personally, it is quite interesting how it ties in.

The model in detail

Next, some more elaboration on the steps and what catches my eye:

1. Preliminary Specification of the User Interface

This is pretty much what you would expect - at least, I think so. Funnily enough,the authors honor this step with one single sentence. The subtext here is probably that people do this one anyways, and should really focus more on the other steps.

2. Collect Critical Information About Users.

Similarly little elaboration needed. What the paper stresses and what may be stressed forty years later still: Do talk to your users directly. Looking up users ‘properties’ based on theoretical data and stereotyping does not really work.

3. Develop Behavior Goals

This one is separated into sub-steps, which are basically:

- Describe the user

- Describe the tasks

- Define a measurement (learning time, errors, attitude, …)

Personally, I think the focus on quantifiable data should be noted. I have rarely seen such a focus on quantifying whatever can be quantified in other models or practical approached. The authors do concede that some things are hard to measure rigidly, but I do nonetheless wholeheartedly agree that there is real value in having clear measures for your design.

4. Organize the Work

Think about who does the backend, the frontend, the manual and the training and make sure that all these people design together and talk!

5. Iterative Development Phase

As you might expect, this is the biggest phase, because you basically do it until your users hitting all your goals. For this to succeed, the authors recommend implementing a process where prototyping and iterating is easy and cheap with little wasted work. I would go so far as to say that they are describing what will be called an MVP approach decades laster.

Closing Words

Well, that’s the model. My intention here is not to offer inappropriate judgement on how good this model is - on the contrary, I simply want to thank the author to broaden our horizon by adding another possible mental model to approach all this UX stuff.

I hope you are taking some learning away from this post as well - be it historical understanding, practical ideas or just some entertainment. See you for the next part, which will be a case study; the final section of this paper. For now, I will leave you with a great quote from Designing for Usability: Key Principles and What Designers Think:

In practice, actual development of a system follows any design philosophy only approximately, regardless of how formal or precisely mandated it is.

Gould & Lewis

Until next time!

Thanks for reading! This post is part of my series of reading and summarizing papers, mostly relating to UX. I use a casual tone because that’s the most fun to me. That means my interpretation of a given paper may be off. Or incomplete. Or plain wrong. Always think for yourself, and please, don’t cite this in an academic context. Use the original article instead. Cheers!