Why do even small challenges feel so daunting sometimes? Why, at other times, we grind through really tough stuff with a satisfying, gritty determination? Why do some people often feel one way or the other? Difficult questions, no easy answer.

However, there is one paper by Dweck which crafts a quite intriguing model to at least start answering these question. It is quite old - 1986 - and mostly based on other literature. So, probably ripe for a shakedown by the replication crisis and newer research in general. Be that as it may, the core idea is so useful as a mental model that I want to summarize it anyways:

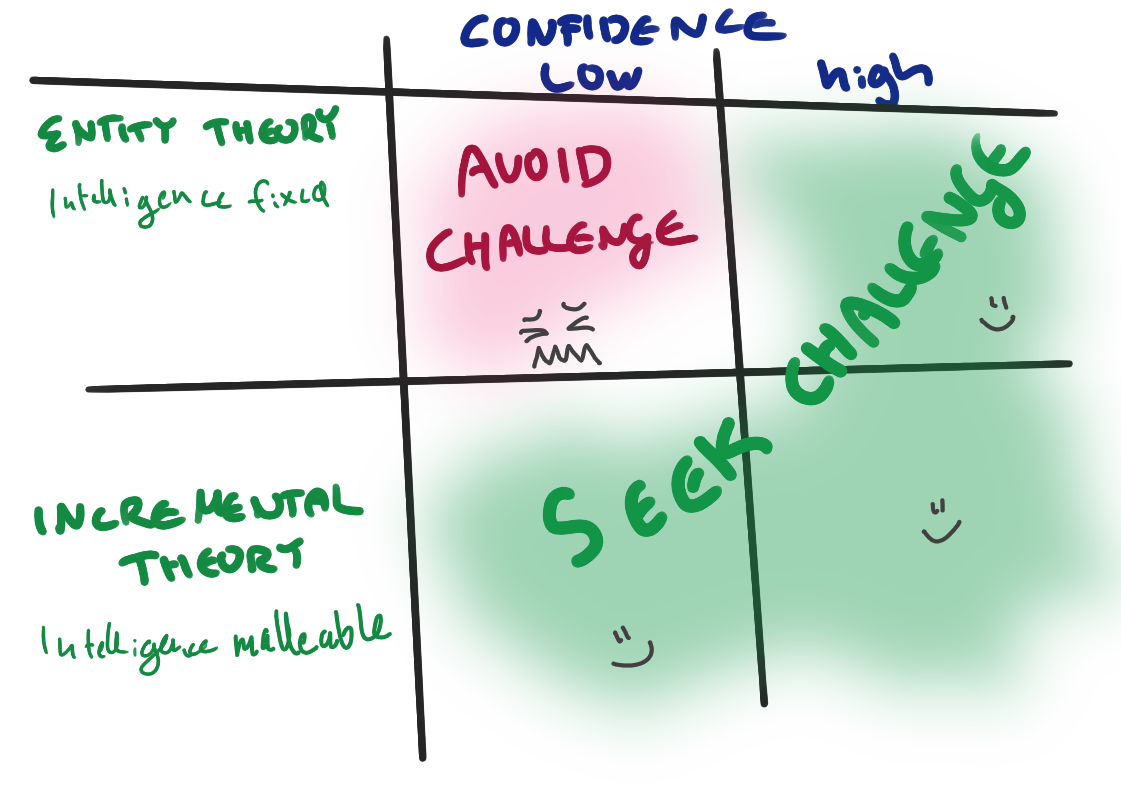

The central idea, sketched

Quite a simple idea, right?

If you think that intelligence (or your ability, for that matter) is fixed, you are only going to seek challenges if your confidence in your ability is high (presumably because you are already good at it). If you think you can improve, you can always seek challenges. If you think you are bad at something and you don’t think that’s ever going to change, you are fucked.

I like it because it’s…subtle. It shows why you can run with a ‘fixed’ model for a long time before being hurt by it. It also shows why adapting a ‘malleable’ model is a generally good idea. It also does not need to do a grandstand on nature-nurture-questions, because it just talks about whether you think that ability is inherent.

There is a lot more to Motivational processes affecting learning - exploration how these patterns arise in children, sex differences and all that stuff. But for now, I just want to focus on this central model, so…this is basically the article.

Just one more nugget: Dweck calls these different intelligence theories adaptive and maladaptive patterns, which I find quite apt and meaningful wording. Will possibly steal in the future.

Thanks for reading! This post is part of my series of reading and summarizing papers, mostly relating to UX. I use a casual tone because that’s the most fun to me. That means my interpretation of a given paper may be off. Or incomplete. Or plain wrong. Always think for yourself, and for the love of God, don’t cite this in an academic context. Use the original article instead. Cheers!